Low inflation and low unemployment. What's going on?

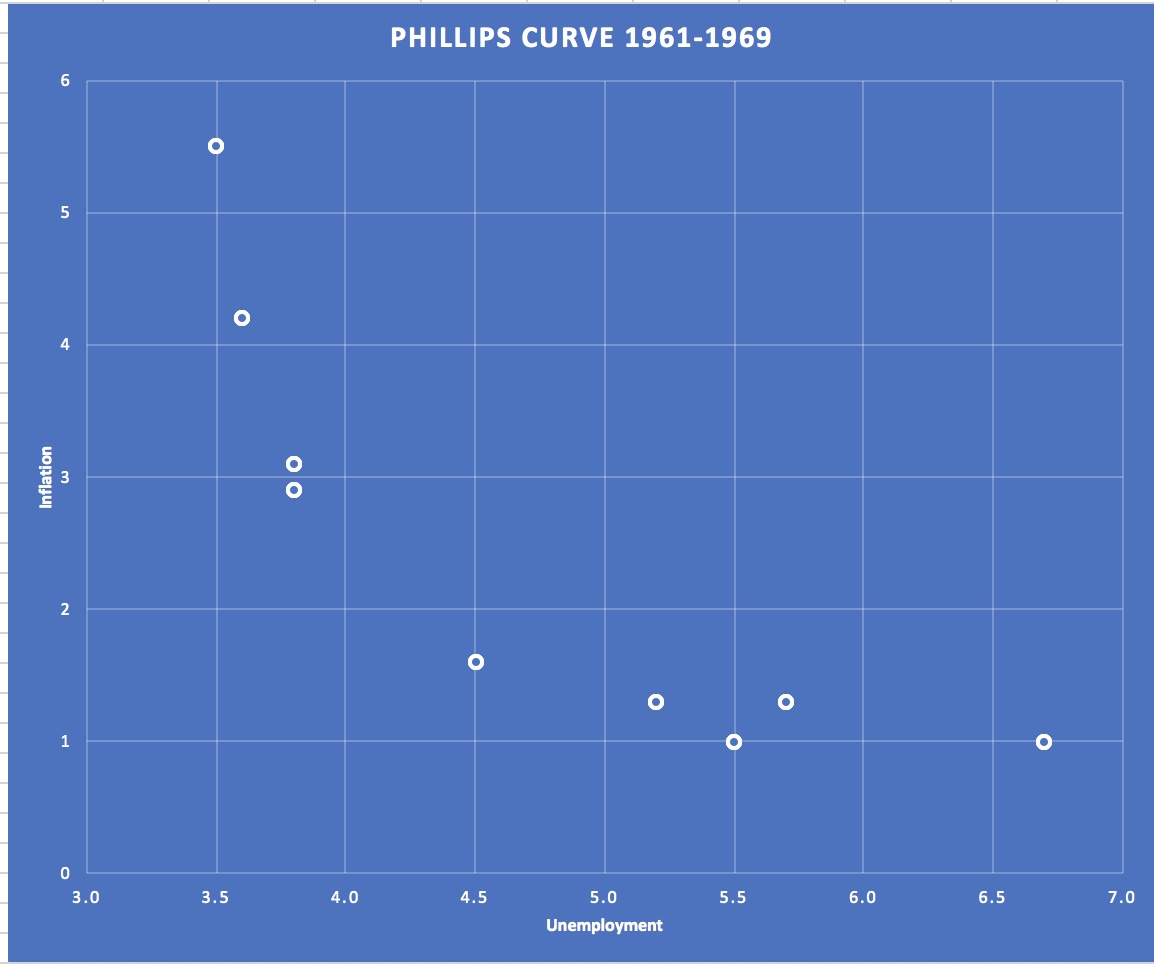

The Phillips Curve was developed in the 1960s, inversely correlating inflation and unemployment. Using data from 1961-1969 here’s what can be observed:

The theory goes that as more people get jobs (less people are unemployed), people have more money to spend, which will drive prices for the same goods/services (and inflation) higher. As a result, the Phillips curve describes an inverse relationship between unemployment and inflation. As unemployment rate goes down, the inflation rate should increase.

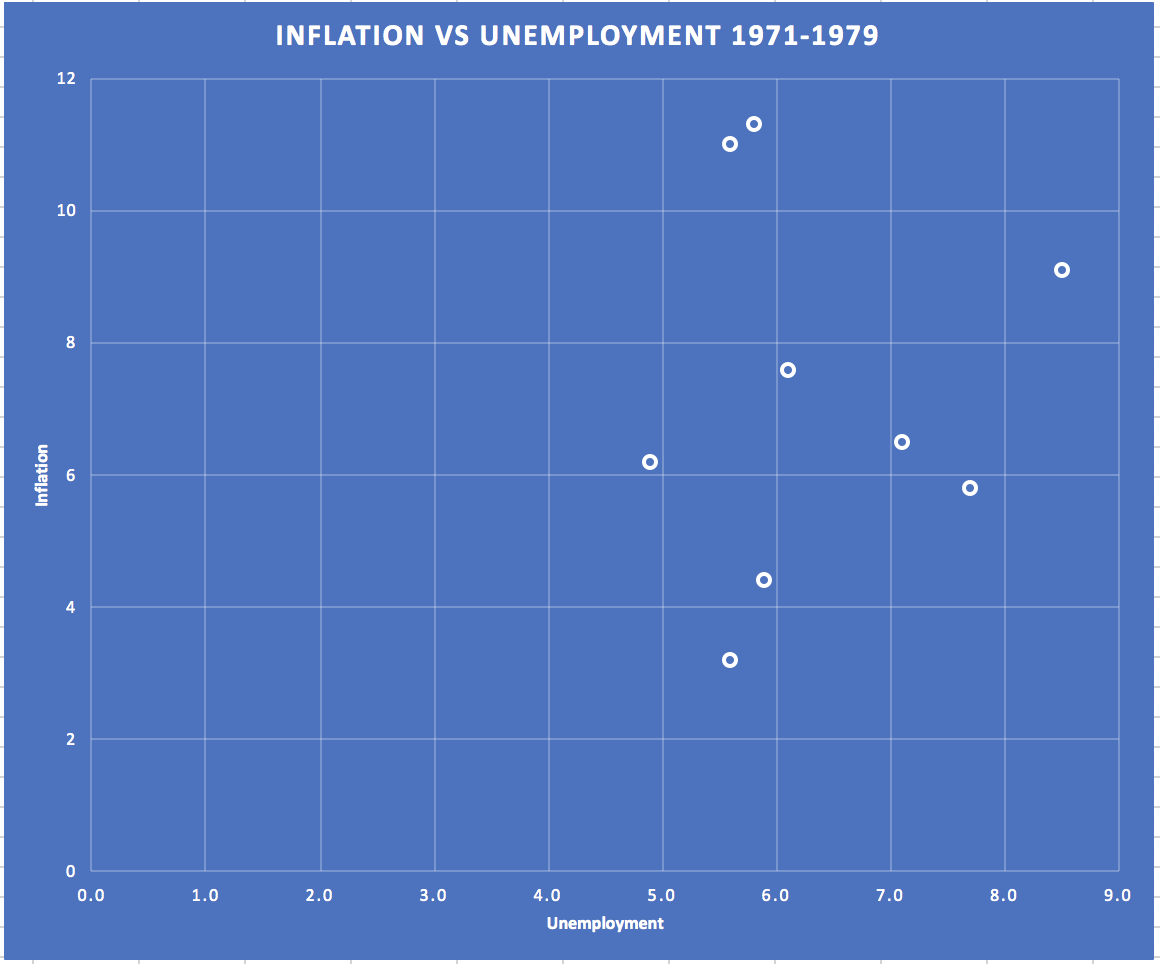

Critics of the Phillips curve use the 1970s to illustrate how this inverse relationship breaks down. During the 1970s there was a period of time where high inflation and high unemployment existed - mostly referred to as stagflation.

Stagflation is mostly dismissed by economists who follow the Phillips curve doctrine as “short run” thinking and over a long period of time, things will normalize back to the inverse relationship. The 1970s stagflation was mostly blamed from the oil price shocks that happened at the same time monetary policies had changed.

Setting aside some of these theories and discrepancies for a second, the US is starting to observe something new. Low unemployment coupled with low inflation.

Recent data suggests that we are seeing record low unemployment coupled with low inflation. What exactly is this called and why is it happening?

If we follow the thought process around the reason for stagflation in 1970 (a supply shock in oil and prices with simultaneous monetary policy shifts), we might think that there is a similar opposite supply shock that’s happening now causing this. Essentially there could be an oversupply of a specific commodity that keeps prices and inflation low, coupled with the low unemployment. An optimist might continue to argue that technology caused these shocks by improving efficiencies within the manufacturing and industrial sectors and these improvements allow corporations to produce more goods and services at inexpensive prices, while employing more workers in the process. I have no evidence that this is the case, but the thesis, if supported, could be a strong one.

My personal intuition is that technology hasn’t improved any of these major industries in such a way to make an impact like this on an economy, yet. It’s much more likely that consumers are spending irrationally or something is overlooked in the financial system. Irrationality doesn’t last forever so when things come to light, let’s just hope that we’re ready for it.